'Abba was somewhat of a dirty word': How the pop band's 1974 Eurovision win divided Sweden

Alamy

AlamyFifty years ago, Abba was triumphant at Eurovision – but a new documentary shows just how bittersweet that victory was.

It's been 50 years since Abba arrived onstage at the Eurovision Song Contest – all satin, spangles and silver boots – and marched to victory with their song Waterloo. In a stroke of luck, this year's contest takes place in Sweden, setting the scene for a suitably glittering celebration of their country's biggest musical export.

Organisers of this year’s event are planning to thank Abba for the music by way of a tribute performed by three previous Eurovision winners: Charlotte Perrelli, Carola and Conchita Wurst. It’s not clear whether we’ll see an appearance from Agnetha Fältskog, Björn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson and Anni-Frid 'Frida' Lyngstad, too. Last year Björn and Benny dismissed the idea of a reunion for the contest, and the band haven’t performed together for over 40 years. But fans are hopeful they might see the band — even if only in the form of the digital avatars that have thrilled hundreds of thousands at the Abba Voyage virtual concert in London.

After all, no other Eurovision winner has come close to matching the success of Abba, who since winning the contest in 1974 have sold 385 million records and become one of the most successful bands of all time. A recently unveiled commemorative blue plaque on the Brighton Dome marks the spot where Abba "launched their career after winning the 19th Eurovision Song Contest". But, as a new documentary about the band shows, the victory was bittersweet, and the start of an uphill battle to get their music taken seriously. "The mythology around Abba has become very much that they were always destined for stardom," James Rogan, director of Abba: Against the Odds – which draws on rare archive footage and interviews – tells the BBC. "Eurovision was a huge milestone on the road to stardom, but they immediately ran into massive headwinds after winning."

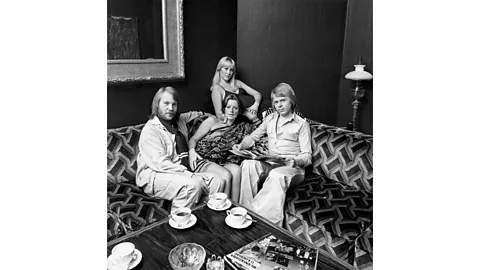

Alamy

AlamyThe foursome formed in 1972, and tried unsuccessfully to enter Eurovision in 1973 with their song Ring Ring. Seeing the contest as their ticket to success outside of their own country, they pulled out all the stops the following year, writing Waterloo specifically for Eurovision. It paid off. Not only did they win in Brighton, but Waterloo was a number one single in the UK (despite receiving nil points from the UK voting jury) and topped the charts all over Europe.

Yet in the film, Benny recalled how the UK initially saw them as "quite beige", saying: "Even if the song was number one in England, if you're part of Eurovision, you're dead afterwards." Radio DJs were reluctant to play the band's music, and it would be more than 18 months before they had another number one with Mamma Mia. Eurovision was proving to be a double-edged sword. The outfits, as fabulous as they were, perhaps didn't help. "We weren't taken seriously, I think because we were wearing such strange clothes," says Björn. "The kitsch… we really suffered for that."

Backlash at home

But it was in their home country where Abba – who shared their name with a Swedish brand of pickled herring – faced some of the biggest animosity. "It was a different mass-media climate in Sweden at that time," says Björn. "We were not popular."

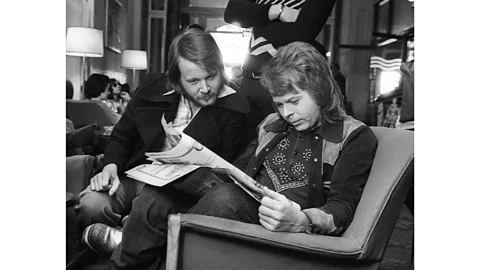

Alamy

AlamyArchive footage in the documentary shows Swedes being asked their opinions on the band. "They're too commercial," answers one man. "They only sing pop," says a woman. The band were viewed by many as manufactured and only in it for the money. Before ing Abba, Björn and Benny were both in popular folk groups, while Agnetha and Frida were successful in their own right. "And then they came together in this kind of glitzy glam bubblegum pop formation," says Rogan, who likens the backlashto the outcry over Bob Dylan going electric.

Another issue was that, as per the Eurovision rules, Sweden was due to host the contest the year after Abba's win. "The fact that they had won meant that [public broadcaster] SVT then had to fund Eurovision," says Rogan. "This musical culture which regarded itself as authentic and sort of folksy suddenly saw the funding dry up for their projects and Eurovision sucking it all up."

A left-wing movement called Progg, which campaigned against the commercialisation of music, protested against the contest coming to Sweden, with 200,000 people taking to the streets of Stockholm. On the night of the show, there was an alternative music festival hosted on the other side of the city. "There was kind of a progressive movement that looked upon Abba as the Antichrist," says Björn. Such was the power of the protests that Sweden decided not to enter the contest at all in 1976.

That Abba were apparently apolitical also riled many. "We were the upset generation," explains Michael Wiehe, singer with Swedish group the Hoola Bandoola Band in the documentary. "We were upset about the apartheid system, we were upset about the military coups in Latin America, we were upset about the wars in South East Asia. And we were upset that Abba weren't upset."

Alamy

AlamyAll this meant that – though they did well commercially – Abba was somewhat of a dirty word among the music community in Sweden. "They were selling a lot of records and were hugely popular," says Rogan. "But those records would then be hidden on the shelves. And some of the musicians who played with them were blacklisted."

This sort of musical snobbery would plague them for years, not just in Sweden but around the world. Even as they racked up hit after hit, the press continued to be wary of the band, with press cuttings in the documentary featuring lines like: "We have met the enemy and they are them."

Looking back over old interview footage, Rogan was shocked by how dismissive some reporters were. "If you had the opportunity to speak to Benny and Björn just after they'd written SOS and Knowing Me, Knowing You, would your questions be: 'How poor are your lyrics? Do you like playing it? Isn't it all a bit samey">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });