How Harry Potter became a rallying cry

Alamy

AlamyPlacards at the March For Our Lives protests on Saturday referenced JK Rowling’s best-selling book series. Hephzibah Anderson looks at how tales of the boy wizard have influenced the movement.

In the 21 years since the first Harry Potter book was published, it might seem like the gap between fact and JK Rowling’s generation-defining fiction has narrowed – in all the wrong ways.

Until, that is, this past weekend.

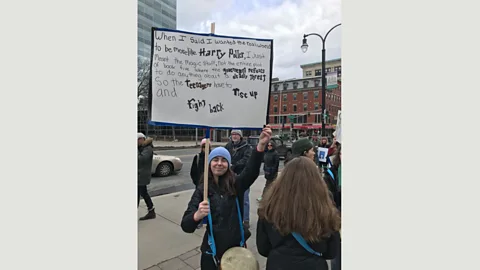

Among the placards that found their way onto social media from the mass March For Our Lives protests one in particular, clutched by a woman in a blue hat in chilly Worcester, Massachusetts, stood out. Its slogan wasn’t the most succinct (just try squeezing it onto a T-shirt in a grabby font), but its message spoke volubly to the moment: ‘When I said I wanted the real world to be more like Harry Potter, I just meant the magic stuff, not the entire plot of book five where the government refuses to do anything about a death threat so the teenagers have to rise up and fight back’.

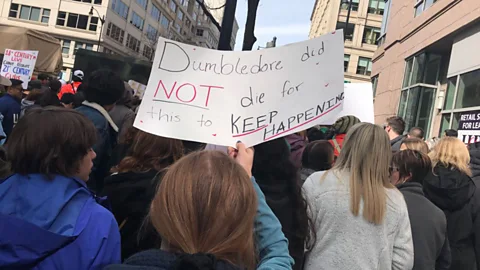

Fight back. There’s the important part, because the ‘Potterverse’ is no longer just a potent source of solace – a kind of literary blankie, as the nay-sayers had it when a newly-elected President Trump began to be likened to Voldemort in 2016. It’s motivating and mobilising its legions of fans, as Time magazine’s Charlotte Alter highlighted in a Twitter thread on Saturday. ‘Expelliarmus!’ ordered a few placards, referring to Harry’s disarmament spell. “‘Expelliarmus’, the disarmament spell, is the go-to spell for Hogwarts kids,” tweeted Alter. “Disarmament is the #MarchforOurLives strategy, both literally and rhetorically.” Other signs across America read: ‘Dumbledore’s Army still recruiting’, ‘Hufflepuffs for gun control!’, ‘Hermione uses knowledge not guns’. As Alter argued in her tweet, “this is not just a generation that has grown up with school shootings— it’s also a generation that grew up reading Harry Potter”.

Peter H Hansen

Peter H HansenNeil Gaiman, adapting a GK Chesterton quote to catchy effect, wrote in his 2002 novel Coraline that “Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten”. To quote yet another sign, held by a schoolgirl protester in a pink anorak, ‘If Hogwarts students can defeat Death Eaters, our students can defeat the NRA’.

Sophfronia Scott

Sophfronia ScottIt’s a sharp reminder that beneath the twee iconography that the series can symbolise to those of us who haven’t fully lived the books – that’s to say, are too old to have consumed them with the intensity reserved for books first encountered in childhood and adolescence – the narrative contains darkness aplenty. Ethnic cleansing and inequality, enslavement, corrupt governments, torture and mind control all feature. In essence, the Harry Potter books are about good versus evil, and battles don’t come more primal than that – especially when the evil in question is fascism. Because let’s not forget that the core narrative chronicles the attempted extermination of Muggles and ‘mudbloods’ by Lord Voldemort and his sidekicks.

Alamy

AlamyIf this resonated when the books were first released, then for the Parkland generation, coming of age in an increasingly nervy world, with fringe groups agitating ever more vocally to make fascism a present-tense threat in Europe and the US, it’s working double-time.

But the use of Potter memes isn’t, as critics like to insist, about the naïve hope that an intractable issue such as gun control can be solved by waving a wand, metaphorical or otherwise. No, as any Potterhead will tell you, Harry and his pals pick up a lot of real-world nous as they take a stand for liberal values and do battle with He Who Must Not Be Named.

Real-world lessons

Sadie LaPonsie

Sadie LaPonsieTake this, for example. Voldemort, flanked by his Storm Trooper ‘Death Eaters’, is obsessed with racial purity, demonstrating a nihilistic sensibility that’s positively Nietzschean. (‘There is no good or evil’, says one of Voldemort’s cronies. ‘There is only power and those too weak to seek it’.) Yet there are myriad shades of grey in the series. As Harry’s godfather, Sirius Black, tells him at one point, ‘The world isn’t split into good people and Death Eaters. We’ve all got both light and dark sides inside us. What matters is the part we choose to act on’.

Another crucial lesson the text teaches is about complacency. The world of Hogwarts is built on slavery thanks to the labours of the house elves. When Hermione finally tries to stick up for them with her S.P.E.W. campaign, she’s mocked by her fellow wizards. Social injustice can very easily become normalised – to the extent that the house elves themselves, with a few exceptions, take affront at any offer of recompense.

Tracy Tran

Tracy TranThe question of whom to respect is similarly nuanced. Though they march under the banner of Albus Dumbledore, there’s an understanding that even he has some blemishes on his record. Yes, there are the outright baddies like bullying Dolores Umbridge, but then what of bumbling, seemingly well-meaning Cornelius Fudge? Again and again, authority is held up as something that should not be respected unquestioningly. (While some critics have accused Rowling of creating a conservative, traditional picture, she has argued that was never her intention.)

Then there’s the importance of a free media and the championing of direct action – small acts always count, sometimes in big ways. But though magic helps and love is Harry’s ultimate secret weapon, on a less showy level, Voldemort is defeated mainly by cooperation and organisation. He has his Death Eaters but the boy wizard has everyone else. that magic disarming spell from the placards? It means we disarm, not I.

This particular lesson is one that the Harry Potter Alliance, a non-profit formed to mobilise fans and campaign against real-world ‘horcruxes’ like bigotry and climate change, has been putting into action since 2005. As the group states on its website, ‘We know fantasy is not only an escape from our world, but an invitation to go deeper into it’.

Alamy

AlamyAnd JK Rowling has herself expressed how her novels embed resistance to tyranny of any kind. “The Potter books in general are a prolonged argument for tolerance, a prolonged plea for an end to bigotry,” she said in 2007. “I think it’s one of the reasons that some people don’t like the books, but I think that’s it’s a very healthy message to on to younger people that you should question authority and you should not assume that the establishment or the press tells you all of the truth.”

This is nothing new, of course. From Greek tragedy to Shakespeare, The Lord of the Rings, even Star Wars – fiction inspires the struggle for freedom. The power of the imagination – of a message woven into a narrative that’s as human as it is fantastical – will always trump a stodgy manifesto.

Alamy

AlamyBut there’s another dimension to the Harry Potter phenomenon. It’s always been as much about belonging and banding together as it has the actual story. The series’ first fans, now in their 30s, queued outside bookshops for the later instalments and saw the pictures of their snaking lines make the news. Their fandom – and that of the young readers who’ve followed them – gave them their first taste of what it is to be part of a story bigger than their own. In a secular, atomised society, that’s powerful stuff. How powerful? We’re just beginning to find out.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.